"Capitalism Doesn't Actually Work" The Story of the Feminist Labor Fight That's About a Lot More Than Housework, Actually

I interview Emily Callaci, author of "Wages for Housework: The Feminist Fight Against Unpaid Labor"

If we’ve ever been in a time when we’re recognizing how capitalism doesn’t actually make sense for providing people what we need to live, I’d say having our country’s public programs torn apart by two businessmen who see only profits and not human beings is a pretty good example. I had heard of Wages for Housework as a feminist movement, before, but I didn’t know all that much about the specifics, or the breadth of the history. (Last year, I even spoke with economist Nancy Folbre about how just estimating the cost of unpaid labor/care work in our society would be beneficial.) The idea of paying women for the work they do at home — the insane amount of unpaid labor that women all over the world are just expected to do — is intriguing, yes, but always tripped me up, too. Because I don’t want a world where women are just paid to do housework and men are paid to work outside the home — I want a world where we can all do whatever we want — without being tied to this capitalist system nor these gender roles. And this whole idea felt too simple in some way.

I was fascinated to be proven totally wrong in my assumptions and to learn about a whole new group of incredible feminists in the book Wages for Housework: The Feminist Fight Against Unpaid Labor by Emily Callaci, an associate professor of history at University of Wisconsin-Madison. Callaci has previously studied and written about African history and the era of decolonization. She had similar feelings to me about unpaid labor, when, after she had her first baby, she was inundated by the capitalist advice machine about how best to get back to work, achieve work-life balance, be efficient, etc. “I really wanted to think bigger about those questions, like, why are we actually in this situation, where this really essential work is something that we’re trying to kind of fit in around the margins?” she told me. “And I wanted to know how feminists had thought about this problem, so I started looking for what feminists had said about this.”

As luck would have it, Callaci began a deep dive into the unpaid labor movement just as one of the leaders of the Wages for Housework movement, Silvia Federici, was putting her archives togeteher at Brown University, in Providence, Rhode Island, which happens to be where Callaci’s parents live. She spent part of her maternity leave letting her son have some time with his grandmother while she toted her breast pump to Federici’s archives to dive into the question of how to “make sense of becoming a parent for the first time politically, and in the world.”

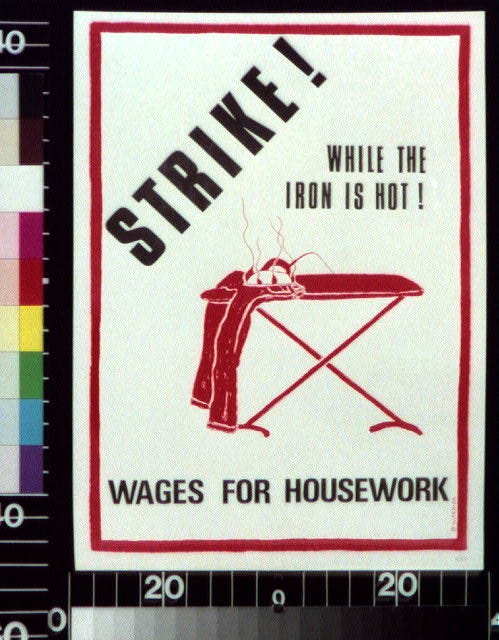

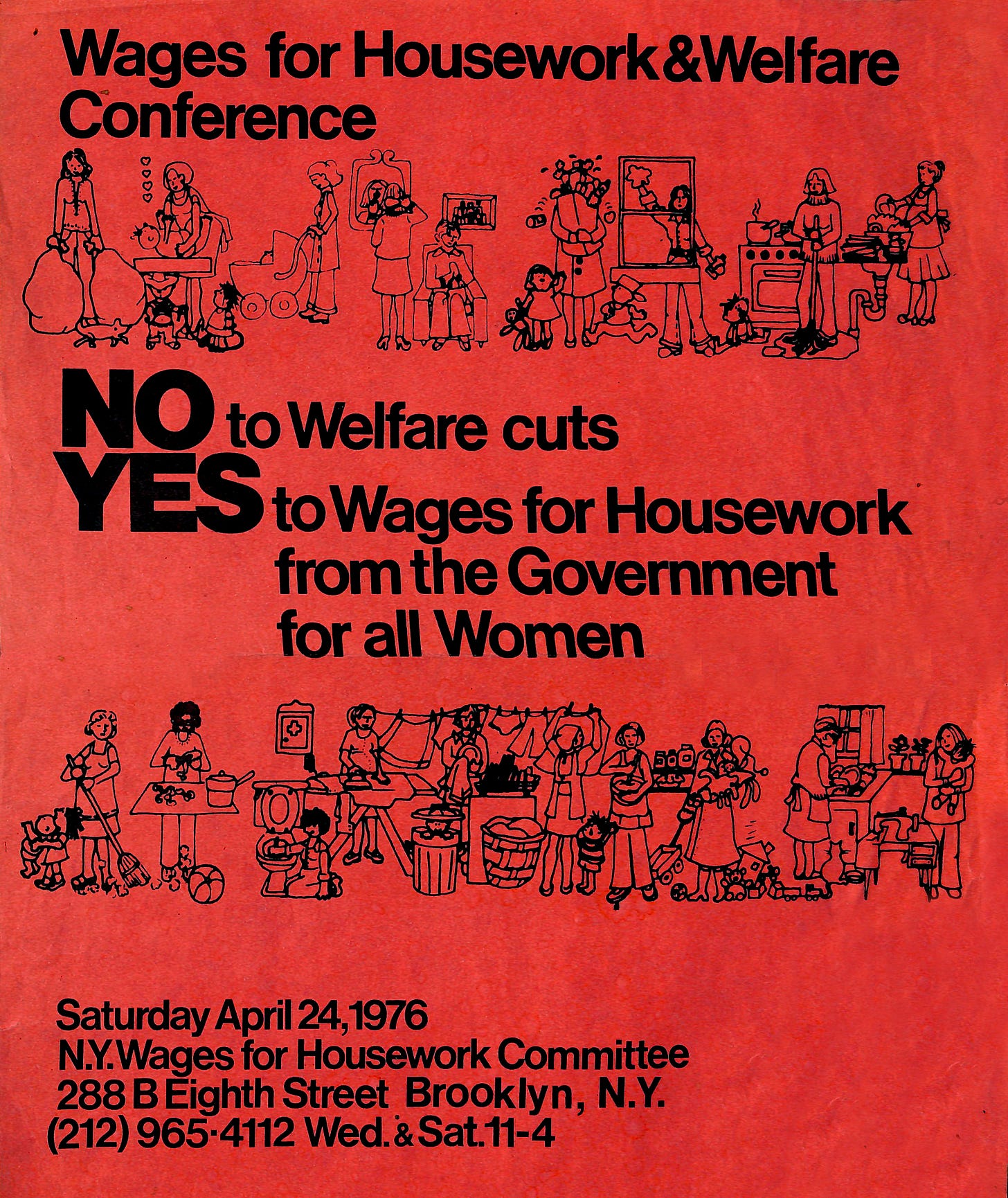

What she stumbled upon, however, was a movement much larger than Federici, herself: a global network of women throughout the 1970s who came together to launch what started as a relatively small political campaign but which turned into an intersectional framework that feminists today can and should absolutely see ourselves in. Wages for Housework is the result of Callaci’s deep and engrossing research into five of the most impactful leaders of the movement, all of whom are still alive and working today: Federici, an Italian-American scholar and activist, Selma James, a working-class Brooklyn Jew and factory worker, Mariarosa Dalla Costa, an Italian student militant, Wilmette Brown, a queer poet and former Black Panther, and Margaret Prescod, a New Yorker from Barbados who fought staunchly for mothers on welfare to be seen as the hardest workers in the world. These women all have gone on to have incredible careers, worthy of the attention Callaci gives, and more. Overall, the book is an illuminating history of feminist activists that should be household names, and a movement that went far and wide to show how much unpaid labor truly exists in our society. We can and should learn from all of them as we find our way forward from this moment when our labor economy and public care programs are being turned completely upside-down.

Callaci and I spoke earlier this week, on the day her book was published here in the U.S. I’m very grateful for her time and openness, especially as an academic at a time when all of higher education is being thrown into uncertainty. Our conversation, below, has been edited for length and clarity.

MAGGIE MERTENS: I knew of Silvia Federici, and had read a little bit of her work, but I didn't know any of the rest of these stories. I learned so much. It seems like one of the central struggles of the movement was explaining why asking for wages for housework is actually anti-capitalist. Can you explain that a little bit?

EC: I think that people in the movement have a few different answers to that, but one of the main points of asking for a wage was that you have to make the work visible, right? If it's not visible within the terms of the market, if you can't show the value it creates, how can you actually launch a struggle against it, right? How can you actually open it up to negotiation? So that was one component: make it visible, so we know how much the economy relies on it.

And then another kind of way of thinking about it — more the branch of Silvia Federici and Mariarosa Dalla Costa, who started the Italian movement — is the idea that there's this illusion that capitalism just makes profit from the person who shows up at the factory or the workplace every day. And if you actually show that the basis of that system that is all this unpaid work that makes it run: producing workers and nurturing and feeding and caring for them. You show that the system is actually not affordable and not efficient. And actually, if you compensated all that work that creates profit, you show that capitalism doesn’t actually work. And making it inefficient can bring it crashing down. So that’s the revolutionary, bigger, longer term, kind of objective.

I think others in the movement would say that it's a first step. Some people thought, well, you demand payment, then you just get paid off, and then you just become a paid housewife, right? That's the end of the struggle. But Selma James and Margaret Prescod, particularly Prescod, had experience with welfare rights movement organizers. The idea was that you demand a wage for it and then you demand more. You keep going, right? It's kind of the first step in bringing about more recognition and more power for those workers.

And actually, if you compensated all that work that creates profit, you show that capitalism doesn’t actually work. And making it inefficient can bring it crashing down. So that’s the revolutionary, bigger, longer term, kind of objective.

MM: Getting the sense of all of the various people who were involved in the movement, from different activist backgrounds and parts of the world, really changed my sense of what the whole movement was about. Of course, these were mostly women working in the movement, as this idea of unpaid, invisible, “housework” is what we typically consider “women's work.” But I wanted to ask you about the role of men. Could you talk a little historically about the role of men in this movement, and also today, does a shifting sense of gender roles today impact this kind of a movement?

EC: Yeah, that's a great question. In terms of historically, as you pointed out, yes, if you look at the pictures of the movement, it's all women. For Selma James, she's from this working class socialist background in Brooklyn. She grew up in a radical Jewish community. She really is committed to class struggle in the kind of traditional sense of the word so for her, she doesn't see this as a departure from that struggle. She’s saying, what the left is missing is that the working class is way bigger than you thought. It's not just the men in union jobs at factories. It's all of their wives and women who are both at the factory and at home. So this is liberating not just for the women but also for the men. She argued that male workers had less power because their wives depended on them financially, and that if women actually had their work compensated, they would be autonomous from men. And then if a man wanted to go on strike, for example, or demand higher wages, he wouldn't have to worry so much that if I do that, my entire family is going to be screwed.

That said they didn't get a lot of men on board with that argument for several reasons. I think one is that, you know, on the left there was this real sense of a traditional Marxist analysis, and women were told those issues are kind of frivolous. And maybe after the revolution comes, we’ll think about your little feminine issues. But for now, get in line behind the men. So there's that latent sexism. But then additionally, this is the 1970s and the unions are really under attack in the UK and in the US. So I think that there was this real sense that when you criticize the unions [at all], you’re bullying the victim.

But there was this moment in this movie that Selma James and the British Wages For Housework committee made in 1970, and they're interviewing all these people about: what do you think of housework? And what do you think about the work that you do? And one of my favorites is they interview this young man who's a new father, and he works full-time, and she's asking him, ‘What do you think about women doing all the housework, and shouldn't you get a chance to do some of that too? Don't you miss this opportunity to know your kids?’ And you can just see this light bulb go off. And he says, ‘I guess I would actually like to spend more time with my children, and maybe we don't want to divide the labor in quite that way.’

MM: I think that is something that we're seeing now with this current generation of fathers, is that that idea is a lot more palatable. That it does make more sense to them to want to be involved with housework, want to be involved with their children, even though I know the statistics are still skewed towards women doing the majority of housework. But I do think there's been a big shift just in the thinking about that.

EC: And I think that’s one of the interesting things I’ve had to think about myself. As you point out, on a global scale, the statistics are still very skewed [towards women doing more housework]. So the issue hasn't gone away. But also, like I also live in a family where my partner is a man, and, you know, there's no making up for gestation and breastfeeding, but at the same time, in our actual lived lives, he probably does more housework than I do. But I hesitate to even say that, because I don't want it to seem like I'm saying, well, we fixed it. I found my solution. So I don't know quite know how to talk about that, but I do want to say that I think the argument for considering this kind of work important and valuable, and giving it more of a place in how we think about organizing our society, I don't think that men doing more of it solves that. I think it's relevant to all of us. In the initial manifesto for Wages for Housework was wages for housework for anyone who does this work.

MM: Right, even if you are splitting up housework more equally in a two-parent home, it's still so much work and so overwhelming, and then you both have paying work as well typically now, and honestly, it’s just not sustainable even on an individual level.

Switching gears, a little bit, you write about a lot of the women in the WFH movement hitting roadblocks with this work around the 1980s austerity movements, which kind of took the wind out of the sails of this kind of a movement for more public programs. And that really makes me think about the current massive cuts to public programs we’re seeing from the U.S. government, and what might be to come in terms of unpaid labor. You write in the book that, economic austerity, in the wealthiest and the poorest countries, means the same thing: More unpaid labor from women. Is there anything that you're thinking about that maybe we could learn from that era or that you're thinking about as as we're kind of seeing history repeat itself in a way?

EC: I was thinking about this a few weeks ago, when they were first announcing all these cuts and layoffs and there was this local NPR story here in Wisconsin, about what these programs do in these small communities. Everything from the kind of things that you associate with government, like public schools and Medicaid and that kind of stuff, but also programs that you might not think of as being connected to federal funding, like Meals on Wheels. Programs that are meant to take care of everybody. And my most optimistic thought hearing that was, nobody is going to watch people in their community go hungry and think, ‘Well, that's okay.’

But the question becomes, does that work go away? Or is the government banking on that they can freeload off of good samaritan citizens to do that for free? Thereby denigrating that work and suggesting that's just women's work anyway and we don't need to actually value and compensate it. Like when you cut school programs for arts and theater, those things just become things parents do instead, thereby making it this thing that some people can access and others can't. So I have been thinking about what kinds of things are going to be no longer be supported, but continue to be done for free, and by whom.

Like when you cut school programs for arts and theater, those things just become things parents do instead, thereby making it this thing that some people can access and others can't. So I have been thinking about what kinds of things are going to be no longer be supported, but continue to be done for free, and by whom.

MM: Another part of the book that was just very mind-blowing to me, was reading about how most of these women really ended up linking this idea of housework to all of these other areas of activism that we might not typically associate with that, like the environmental movement and the anti-war movement, and one woman discussed “the housework of cancer,” which I thought was such an incredible phrase. And I found it to be a really profound example of intersectionality and the way we can think about how these struggles are all connected. Was any of that surprising to you that these women had moved in all of these different areas?

EC: Yes, you talked about the “housework of cancer,” that's Wilmette Brown. And that is the thing I read that blew my mind, when I read this pamphlet that [Brown] wrote, which I found in Silvia Federici’s archive, and it was about her experience growing up in Newark, New Jersey, a very industrialized zone, and they have the highest cancer rates in the country because of the toxins there from the chemicals that produced Agent Orange for the Vietnam War. So there are these incredibly high cancer rates in this predominantly Black neighborhood, so environmental racism is behind that. And when Brown got cancer in the 1980s, she'd already been involved in Wages for Housework, and thinking about how housework is relevant, particularly to Black women and queer women like herself. And then she started thinking about the incredible amount of care work that is required to survive cancer, and to care for people who have cancer, and to have cancer in your community. And all this work is unpaid and basically imposed upon you by things like environmental racism and state neglect.

So for me, the big aha moment was thinking that, Wages for Housework up until that point had talked about ‘housework as the work that makes all work possible.’ But she turned that on its head and said it’s not just that, it’s also the work of surviving these kinds of harms, and of caring for communities that have been victimized by those kinds of policies and those kinds of violence. So, I found that stunning.

Brown goes on to connect her own experience of being a Black woman cancer survivor from this part of the country that's experienced environmental racism, to thinking about this as a global issue. She’d already been an anti-war activist, but she went on to join the board of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. And she would talk about the people who have experienced the environmental impact of radiation, and where uranium is mined, and the people in Vietnam who are caring for people that were exposed to Agent Orange, and she connects all of it to women from her community whose sons get drafted and then go to war and become ill or get killed. So she really takes housework and the kind of care for human beings and ecology and just explodes it out of any idea that this is just a nuclear family thing. And that was really the moment that just hooked me to this.

MM: It's a wonderful re-frame to think about housework beyond the nuclear family, which often I interpreted as a way to further empower middle class white women to have careers outside of the home, but couldn’t really see beyond that. But when we can look at it as all of this other care that is necessary across communities to survive our society, that just feels like this movement has so much more opportunity. Speaking of that, I loved the idea that Dalla Costa brings up toward the end of the book about feeling burned out from fighting against things all the time, and wanting to fight for something. That felt really resonant in this present moment, when everything feels really reactive and there's a different emergency every day to respond to. And I wonder if you feel like there's room at this moment, to fight for something?

EC: One of the things that I find really useful, particularly in terms of an organizing principle, is how one of the guiding principles of Wages for Housework is that we all have a relationship to housework and care work. Some of the original members of Wages for Housework that are still together today, organizing Selma James and Margaret Prescod, in particular, and now the others that have joined them, they have reframed Wages for Housework and started calling it Care Income, which grew out of the pandemic, trying to be more inclusive, to supporting all kinds of care work and essential work all over the world, including you know women in the Global South who are living with the effects of climate change and trying to protect their environment.

Silvia Federici has been really involved in the idea of re-commoning, taking things that have been privatized, and reclaiming them as common goods and spaces. I think there’s a lot of potential in that idea as well.

And then more generally, I see Wages for Housework taken up in all these kinds of different areas, such as, for example, programs for universal basic income. There have been a lot of pilot programs, for example, that are specifically targeting parents and new mothers, particularly single mothers. And I think it's really great when that is called income for the work of care, rather than simply seen as a benefit, which can be degraded as charity, and as freeloading. This really recognizes that parents are actually doing essential work and it should be compensated. I've seen advocates that really talk about reinvesting in the kinds of work that sustain life and sustain communities, rather than the kinds of productivity that extract from the environment. One of the places I’ve been most excited to see that is from the prison abolition activist, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, who has been really critical in talking about investing away from the prison industrial complex into community care, basically. And she's someone who actually was in a study group with Wages for Housework in the 1980s, so she has this kind of link between the two. So for me, there are all these different ways that that idea of recognizing essential unpaid work can really change our politics.

There have been a lot of pilot programs, for example, that are specifically targeting parents and new mothers, particularly single mothers. And I think it's really great when that is called income for the work of care, rather than simply seen as a benefit, which can be degraded as charity, and as freeloading. This really recognizes that parents are actually doing essential work and it should be compensated.

MM: At the end of the book, you wrote about this idea of how the lexicon has kind of moved into this broader topic of “care work” which might be more palatable to people than “housework,” but that referencing “housework” specifically is still important to you. Can you just explain a little bit about your thinking behind that?

EC: I think there were two reasons for me really kind of coming around to “housework.” One was, some of it is just shitty work. It’s not all sublime or rewarding. Someone has to clean up the puke on the floor, or change the bedpans. So when we try to elevate it to this sublime thing, which can be a wonderful thing for the most part, but it can also separate out the most prestigious, rewarding forms of that work from those who do the less romantic parts of it. And then another reason is that I like that it connects me to this longer lineage of women. I think we can have this tendency to think, ‘Well, I'm totally different from, you know, the feminists who fought for this in the 70s and the 20s. I'm liberated!’ But I think it's also really important to see yourself as connected into a longer process of struggling for liberation or something. Does that make sense?

MM: I think it does, actually. And I think that's why I loved learning more about this movement, to see I could relate to it more than I might have initially thought. Sometimes I think we think of our ancestors as these women who were toiling away, and cleaning their houses and cooking the meals and not doing anything outside of that except dreaming of office jobs, but in reality so many were part of these communities and thinking about their environments, and their neighborhoods and politics. I think oversimplifying the past is a very easy way to assume we in the present are totally enlightened and everything is fixed. Speaking of bringing the past to light, correct me if I’m wrong, but this feels like the first comprehensive chronicling of the Wages for Housework movement. Why do you think this hadn’t been done before? Just reading about these women I kept thinking, why are these not all household names?

EC: Maybe the most nuts and bolts reason is that I was lucky that a lot of people were starting to make their archives available right as I was becoming interested. I imagine there will be more books about this. Another reason, though, is that, you know, these women, they did not part on good terms, and there's a lot of pain and disagreement in this history. So that was something I didn't realize at first, and that was a real part of the work for me, figuring out how to actually write this story when these women have grievances against each other, and I'm trying to listen to all of them and tell their stories, but without participating in the disagreement. I had to really learn how to build relationships and trust throughout this and to try to kind of hold my own as the writer, because I don't think a complete history of this could not, for example, tell the story of Mariarosa Dalla Costa, or the story of Wilmette Brown, so that was really challenging, and I feel like that might have been a deterrent to some people, possibly.

MM: It sounds tough. I sympathize with you. Because that kind of thing can really put you off of something if the people aren’t really on board. How did you thread that needle in the end? I know you spoke directly to many of the main figures but not all of them. Was that just in part because those emotions were so high?

EC: So I ended up structuring the book around five women in particular. Mostly for the reason that I thought these five women had really distinctive things that they offered to Wages for Housework, in terms of their backgrounds and their political experiences. But I also thought that structure would allow me to lay these stories side by side, and let the reader see the disagreements, without having to be the judge in any way. In terms of the process, I spoke with all of them, except Wilmette Brown. Well, Wilmette I emailed with, but I spoke with everyone else, although some were definitely more forthcoming in conversation than others. And some I spoke to many times. What I did in the end was basically allowed everyone to read the parts of the book that were about them, but not about each other. That way I feel like people could see how they're being represented, what they had put on the record and how I interpreted it, but they weren't going to be able to kind of weigh in on how the others were written about.

MM: I feel like you could see on the page that this was an emotional situation, that was really complex, and also that this kind of thing is very common. In political work or activism work to have those kinds of disagreements that do feel really intense personally or emotionally and might end a movement in some ways, but you can also see that everyone involved is doing what they think is best. Have you heard from any of them since the book has been finalized?

EC: The book was actually launched in the U.K. a month ago, and I had sent Selma James the chapter about her, and when I had a full version of the book I’d sent it to her. And I went to England when it launched and didn’t know until I showed up in person whether she liked the book or not or whether she was going to tell me off, but when I arrived at the Women’s Center, they had food and wine and chairs set up, and it turned out to be a book party I didn’t actually know was happening. That was really moving. They were really, really happy about it.

Thanks for reading! My So-Called Feminist Life is a newsletter wrestling with feminism in today’s world. I encourage conversation in the comments if you wish to share your own thoughts, feelings, memories, opinions. If you’d like to support this project financially, you can become a paid subscriber.

You can find me on Instagram: @maggiejmertens and on BlueSky @maggiemertens.bsky.social

You can order my book Better, Faster, Farther: How Running Changed Everything We Know About Women (Algonquin Books) from your favorite local bookstore, request it from your local library, or push this quick order button from Bookshop.org. If you’ve read it, I’d love if you’d leave it a glowing review at Amaz*n or Go*dReads.

Very ver interesting!!!!