A Feminist Archivist Explains How Data from the Past Shapes the Feminist Future

Ask an Academic is back, with Marika Cifor of University of Washington

Maybe it’s a defense mechanism, but one of the ways that I’ve felt able to cope with living through “unprecedented times,” (again, and again, and again) is to consider how our actions today will one day be in the history books that our children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren, and/or other future kin read.1 That we, in some small way, do have the power to impact these giant turning tides, or at least to make our voices heard, to push things in even the tiniest bit of a better direction.

But the question lingers, of course, as someone who has spent nearly a decade now researching and writing about women who were left out of the historical record entirely, what version of history will those future young people learn? Whose stories will be archived and how will they find them? Especially in this moment when many of us act as though the thoughts we emotionally post to social media platforms are our historical legacy, I worry that we aren’t taking the right precautions to leave a more substantial trace as those of us who disagree entirely with the things happening in the highest halls of power.

After spending so much time in recent years researching and writing a book about the progress made in how we view gender stereotypes, I’m feeling a kind of disbelief about the current discourse around gender happening at a feverpitch. Suddenly, the exact issues I’ve been recording from nearly 100 years ago — like, for instance, the false notion that women are fundamentally less physiologically capable than men — are exactly the ideas that the current ruling political class want to entrench in law.2 And I’m reminded, for the billionth time, that yes, the moral arc of the universe is bending, but it is far far from it’s zenith. We’re still riding this rainbow, folks. And that’s because nothing really changes all at once. There are always marginalized voices. Resistors. Protestors. I’ve been thinking a lot about how while many of us were taught a story of a Civil Rights movement that held up Black activists as national heroes, most of the stories we heard completely ignored the fact that those very same heroes we celebrate today were seen very differently during their present, to the point that they were often targeted by our very own government. We have to dig to find those stories. Humanity is not and never will be a monolith, which is why looking for those stories that do show our ability to change, progress, and resist feel ever more important to me now.

To help me in this quest I started to read about the idea of feminist archival work. Several months ago, (before my book came out and when I thought I’d just continue to have the time and energy to write weekly newsletters throughout the Spring and Summer, oops!) I spoke with Marika Cifor3, a professor of information sciences and women and gender studies at the University of Washington. What drew me to Cifor was her writing on how archival work can be feminist.

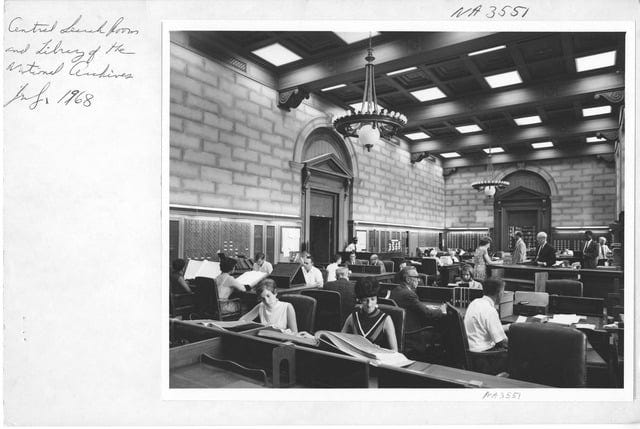

I spoke with Cifor during the waning days of the 2024 academic year — this May. So, back when many colleges and universities were experiencing massive student and faculty protests via encampments against the Palestinian genocide. At one particularly ironic moment, Columbia University’s website boasted an anniversary story based on their own archives of the 1968 student protests against the Vietnam War. The story noted that when the school called the NYPD on its own students it was in the wrong, and the university was “a very different place today.” Of course, in 2024, the school again called NYPD on its own students, resulting in dozens of arrests. Obviously, this moment put a fine point on the importance of how we remember history, whose voices we hear, and how archives can guide us in figuring out how to build a better future in this messy world. And now, six months later, I’m actually seeing even more resonance in some of the topics we covered below. Read on fellow library and history nerds!

Share your favorite story about feminist information gathering or archiving in the comments below.

The following has been edited for content and clarity.

MAGGIE MERTENS: I'd love to know how you got into into this field. It feels like a very specific corner of library sciences. What brought you in?

MARIKA CIFOR: I'm not sure I had actually encountered archives until the end of my undergraduate degree, which was at Mills College, and I was working on my thesis in history. After college, I had a boring but well paid job as a legal secretary, and I started thinking about what I could do with my academic work instead. I knew I didn't want to be a history teacher, but wanted to know what else I could do in that space. I had come out in college as well, and was living in San Francisco at the time and got hooked up with volunteering at the GLBT Historical Society. I started by transcribing a series of oral histories with people living in the Tenderloin in San Francisco, in the midst of rapid gentrification and change. And that was my entry point into doing archival work. And I think it was an interesting entry point for many reasons, because the GLBT Historical Society is a community based archive, which I think is not always people's entry point into archives, certainly not usually an academic’s entry point into archives. And so they both kind of do things along the lines of traditional archival practice, but also collect more expansively.

So traditionally, archives collect original, unpublished materials, generally, paper based materials. Objects are usually considered the purview of museums. But community based archives don't always make those distinctions. And certainly those distinctions don't always work the same way in a digital context. But I got very interested in questions about how we document queer life and questions about what brings us together as queer people, beyond strategic political alliances, and I would say it's about feeling, and affective relationships and things that are difficult to capture in kind of paper based documents. And so for me, as an academic, that's always been an essential part of my work is thinking about how do we document parts of the human experience, specifically queer experience, that are so fundamentally difficult to document in records? And what can our relationships to the past more broadly tell us about our present and how might we shape our futures, especially for people people from historically marginalized communites.

MM: I love that you described what an archive is, based on like this idea that it's usually paper things, and that can change depending on institutional versus community archives, but I wonder if you could give a basic primer, especially today, when we have so many digital archives ourselves, all of us, what is an archive? Does it have to have an official designation? Has that definition changed?

MC: There’s an argument that what really separates just a collection of digitized things or a website that tells us things from a digital archive, is the kind of archival thinking about context and about endurance. Different people in my field have very different opinions on this strict definition. I think, even if an archive doesn’t collect physical records, they think very critically, and they have policies and context, and long-term preservation plans. Which is very different than me putting up a bunch of things online as an individual, not that an individual can't also have those kinds of plans.

There's this idea that maybe in a digital world we can keep everything and historians of the Internet have two opinions: we're gonna have so much more from this time period, or we're gonna just basically have nothing. Because for people who work on early Internet history, the only things that have survived are what people actually printed out. We actually know a lot less about preserving digital objects than we do about physical ones.

I am always trying to get students to stop thinking about the digital as a kind of immaterial thing. And I think that the emerging discourse in my field about things like climate change confirms this. Because digital archives don't take up the same physical storage space, but they are reliant on data centers and things that have a very real physical, material impact as well.

MM: I feel like there's always been this sense in my lifetime on the Internet that, ‘Oh, if you put it on the Internet, it's gonna live there forever.’ And it's actually like, so many websites and platforms cease to exist or get lost, and I don’t know where a lot of my early Internet history went at all!

MC: Right. The Library of Congress was going to preserve all of Twitter. And at one point that just became totally unfeasible. And then there’s also a question of even if you can preserve it, how do you actually make it accessible and usable? And there's lots of important ethical questions around third party privacy in archival collections. And that becomes much more so in a much larger corpus of data, like all of Twitter than perhaps a few letters from someone.

MM: I know that you you've written a bit about critical feminism as being important to archives and also kind of vice versa. Can you talk a little bit about how those ideas intersect?

MC: I mean, I think for feminist activists today, it can be important to learn about the direct impact of the strategies of people who came before them. I think some archives have been really proactive in thinking that way. I know, for instance, the Sophia Smith collection, at Smith College, has had a fellowship specifically for activists to come engage with the archives. And activists have not always been, at least at institutional archives, that kind of core constituency of users unless we're talking about people who are both academics and activists. But there's been really proactive attempts to think about what we can learn directly from and take inspiration from, like for example, the long history of the strategies that have been used during the fight for reproductive justice. And also, how not to be discouraged by some of the kind of long histories of these things we continue to contend with.

I think our relationship as feminists to the kind of past feminisms fundamentally shape how we understand the moment we live in, but also how we formulate and work towards and make progress towards the kind of future that we want. Archives are a kind of stand-in for thinking about our past. The past that was actually there, and the kind of past that we imagined or desired to be there, and that all fundamentally shapes the future, and the kind of politics we can have in the present. And so I think I see them hopefully as co-constitutive forces.

And there is, of course, a set of archives that operate from very explicitly feminist principles, where teaching other people archival skills, and building community roles, and preservation of objects, becomes more about cross-generational learning. I've always interested in how people document their work as they're doing it and why they choose to do so. And I think one of the things that was fascinating during my last book project was talking to people who had been engaged in movements like ACT UP, about how and why they saved their records, and then how they made the decisions about whether those records belong in an archive, and which archive. Because placing materials in a particular context, like including lesbian history in a feminist archive, fundamentally shapes the kinds of relationships that they have to the other records they are surrounded by.

When I teach the undergrad class on race, gender, and technology I often use as a starting point, a book called Data Feminism by Lauren Klein and Catherine d'Ignazio. And they offer a definition of feminism as, not just an ability to critique the kinds of oppression that has brought us here, but the ability also to imagine something different. Which I think often, the kinds of systems we move in don't want us to imagine otherwise. And having a relationship to our past is an important part of that imagining, that might allow us to actually do the work to make our present and future different.

“I think our relationship as feminists to the kind of past feminisms fundamentally shape how we understand the moment we live in, but also how we formulate and work towards and make progress towards the kind of future that we want.”

MM: In this moment, where we may or may not be surrounded by far too much information, in your opinion, are there still certain groups or stories that you feel like are not leaving behind the trace that others are for the future, groups who are still not being archived?

MC: Some people have the time and space and resources to document their history in ways that other people don't. And I think when people are striving for the very basics of existence, thinking about one's archive might not be the top of one's priority list. For me, I often think about the HIV/AIDS epidemic, in which we have this really remarkable and important body of records from this one period of the epidemic, in the U.S. at least, from 1981 to 1996. So kind of coinciding with the recognition of the epidemic, and coinciding with a period in which we were able to get more effective treatments. So we really have this roughly 10 year history, that will be very, very well documented. Obviously, still with meaningful gaps around race, around gender, around class around immigration status, around language. It's an imperfect picture. But there's a lot of records from this one period of time. And then I think about what will happen from 1996 to the present, where there is still an ongoing epidemic, and AIDS has always disproportionately impacted people who are marginalized, but that becomes even more so the case. Now Black, Indigenous, multiple-marginalized peoples are most impacted. And I seriously don't think we will have the same kind of record that we do from this weird, earlier, period of time. And so that's obviously just one example.

And when it comes to digital technologies, I mean maybe there is democratizing potential perhaps. But I think also lots of archival-oriented creation now happens on private platforms that we only have so much control over. And what happens when those platforms fall out of favor? I often talk about Tumblr, which had this kind of heyday and still exists but doesn't have the same kind of popularity anymore, and then a policy change happens and you lose data. Or questions about X, which most recently was kind of the easiest place for social media researchers to work and had this large user community. But what happens when it falls out of favor, either by their own actions in the space or for other reasons4. What happens to the different social media platforms with their terms of service? Agreements that very few of us ever read, but they do actually often state whether you can take material that's been put up there, can you move it or migrate it elsewhere? Also, if you wanted to donate those records to an archive, would that even be possible? So there's this great potential for people who may not even think about what they're doing precisely as archival, but having platforms involved creates many different challenges when we’re talking about it.

MM: Speaking of the Sophia Smith Archives, I went to Smith College for undergrad, and I was just recently there for my reunion. And I got to see the archives, which they’ve just redone because there’s this whole new library and it’s just beautiful. Anyway, I was looking at these things about when I was at school that they’d kept in the archives, and thinking, wow, there’s so much more to this story than just these flyers, or whatnot. And then I was talking to some of the current students who were all mad at the administration, because of the recent protests and the way they reacted, even though as an alum I had the impression like of course these protests were respected and part of the Smith tradition, etc. But I guess this just got me thinking a lot about the institutions who own archives and how that impacts what we retain from the past, too.

MC: I often talk about this as two different things: One is like archiving activism, and one is activist archiving. And archiving activism doesn't necessarily mean the politics of the institution archiving that activism are all in line with things that that they are documenting. Whereas activist archiving is very much about the use of those records for political work. And when we think about a longer history, pre-20th century, many people only appear in records when they have an intersection with an institution, like court records or the census. So the politics embedded in the collection may or may not mesh with the politics of those embedded in the institution. Often actually, in university collections, students records are often not as well documented as other parts of the university. Because students are there for such a relatively short period of time, and they don't always have a friendly relationship with the administration. They're not really part of a formal records management plan, like for instance, the president's office. But yes. Students, despite being obviously a huge part of campus are not always the best documented, right?

MM: Obviously this brought to mind that during the Columbia encampment, the university had on their website, images from the 1968 student protests and an article celebrating the students and saying the administration made the wrong call in hindsight to call in police and arrest them. Then at the same time, the current administration was calling the police to arrest the student protestors of the day. In other words: extreme dissonance between the archive and the current moment.

MC: I mean, administrations are much better at looking back on and praising a history of activism, but that doesn't always tie to enjoying present manifestations of campus activism. And it begs the question, too, for all of us who work in institutions, how much does the politics of the institution actually represent our own politics?

MM: If somebody is interested in finding an archive on some topic that they want to know more about or something like that, what's your suggestion for how they might go about that in terms of balancing institutional views versus more community type archives?

MC: I wish it were easier. There are some great tools like Archive Grid, which is a database that allows you to search across multiple institutions, but again, you're going to search the institutions that have the kind of resources to contribute to finding aids and other tools. But I do think it continues to be a challenge to just find archival projects. Finding some groups that are engaging in the kind of issues you're interested in and trying to trace from there is one way. Universities in most regions, like University of Washington here in Seattle, collect on all sorts of social movements, and have archivists who are excited to talk to people about their materials. And I think archivists overwhelmingly are very enthusiastically excited about getting people engaged with their materials. And of course, a collection may not be called an archive, sometimes they might be museums or historical societies or projects or embedded in bigger organizations. But if you're interested in an organization, it's worth talking to them about whether they have a collection somewhere.

Upcoming Events, Appearances, Etc.

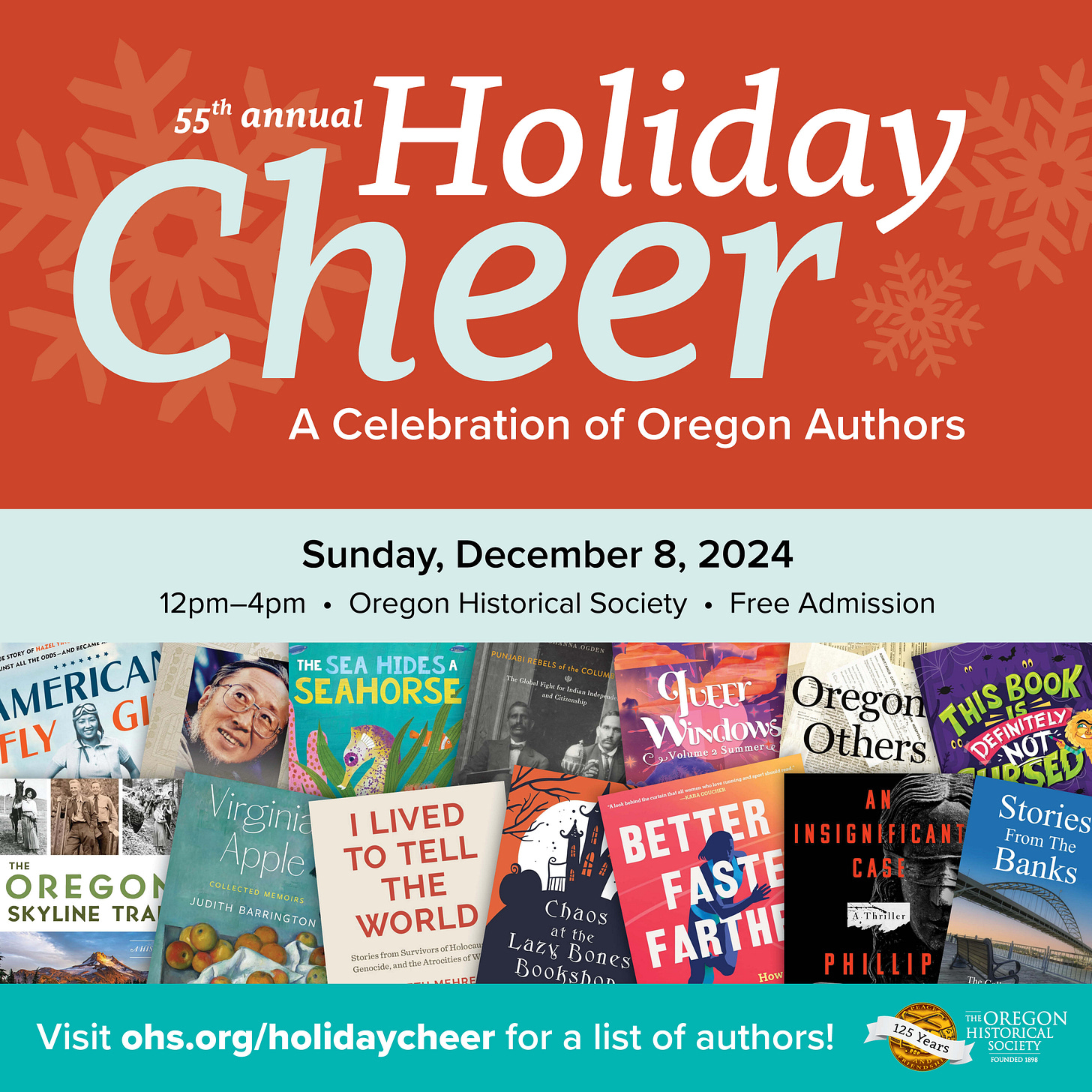

PORTLAND | Sunday, Dec. 8, 12-4PM | Oregon Historical Society Holiday Cheer Book Sale

SEATTLE | Tuesday, Dec. 10 | West Seattle Runner, Women’s Workshop

Thanks for reading! My So-Called Feminist Life is a newsletter wrestling with feminism in today’s world. I encourage conversation in the comments if you wish to share your own thoughts, feelings, memories, opinions. If you’d like to support this project financially, you can become a paid subscriber.

You can find me on Instagram: @maggiejmertens

You can order my book Better, Faster, Farther: How Running Changed Everything We Know About Women (Algonquin Books) from your favorite local bookstore, request it from your local library, or push this quick order button from Bookshop.org. If you’ve read it, I’d love if you’d leave it a glowing review at Amaz*n or Go*dReads. I’ve heard that it makes a great gift for a feminist, runner, or history buff on your list.

OK, also I am running a lot.

I know. For more on that, you can read here.

Here is far more about Marika, including her book and other publications

helpful perspective, thanks ... shines the light on our footsteps and slippages to date.

This is really informative, thanks!